“Set of Makara Brackets” has been added to your cart.

View cart

-

RESERVED

Kerala

Wood, extensively polychromed

An exceptional carved figure of a Kathakali dancer representing Kiratha (Shiva), with finely detailed headgear and costume.

Kiratham Kathakali is a powerful Kathakali performance based on Kirātārjunīyam, depicting Arjuna’s encounter with Lord Shiva, who appears as a hunter (Kiratha) to test his devotion. A dispute over a slain boar leads to a fierce battle, where Arjuna is ultimately defeated and realizes Shiva’s true identity. Pleased with his perseverance, Shiva grants him the divine Pashupatastra (weapon). Known for its earthy Malayalam verses, Kiratham appeals to both connoisseurs and laymen alike. It is deeply devotional, frequently performed in Shiva temples, and is typically the final story in an all-night Kathakali performance, making it a climactic and spiritually significant act.

Kathakali, a dance drama unique to Kerala, emerged in the 17th century, evolving from ritual theatre traditions and Kutiyattam Sanskrit drama. Rooted in Malayalam adaptations of the Ramayana and Mahabharata, it was traditionally performed in temple courtyards or patrons’ homes from nightfall to sunrise, often during harvest festivals or as summer entertainment. Accompanied by temple music with a unique singing style, bronze gongs, cymbals, and drums enhance the performance’s intensity. Kathakali is distinguished by elaborate costumes, ornate headgear identifying heroes and demons, stylised movements, and striking makeup in green, red, yellow, black, and white.

Size (cms): 28(H) x 14(W) x 10(D)

Size (inches): 11(H) x 5.5(W) x 4(D)

-

Gujarat

Wood with traces of polychroming

One of the most abiding images in Indian art is that of Krishna the flautist standing with his legs crossed at the ankles and playing the flute. He wears a decorative mukuta or crown, a dhoti and various necklaces, bangles and anklets.

The image of Venugopala rather late in Indian literature and art and it has been suggested that the classical myth of Orpheus may have exerted some influence. The idea derives from the lonely shepherd who plays his bamboo flute (venu) while tending his flock. While other cowherders f Braj hold a shepherd’s staff, Krishna’s staff is also his flute. He, however does not play upon it to please the cows, but to charm the gopis or cowherdesses

Size (cms): 24(H) x 7.5(W) x 6.5(D)

Size (inches): 9.5(H) x 3(W) x 2.5(D)

-

Andhra Pradesh (South India)

Wood, polychromed

These horse brackets once formed the two ends of a door lintel. The horse or ashva was a very popular motif in architectural wood carvings in South India. Its prototype, the divine Uchchaihshravas emerged from the churning of the ocean. It was white and endowed with wings. The god Indra appropriated it and, after cutting its wings to ensure that it would remain on earth, donated it to mankind.

The horse played a pivotal role in establishing the supremacy of kings, as demonstrated, for instance by the great horse sacrifice, the Ashvamedha, which might have been established in the course of the Vedic period. Equestrian motifs appear prominently in Indian art, for example in Orissan sculpture of the 12th and 13th centuries, and in that of the late Vijaynagara and Nayak periods (early 16th to early 18th century) in southern India. There is a branch of literature specialising in the training of horses, which contains detailed passages on colouring, proportions, gait, auspicious and inauspicious marks and lists of appropriate names for horses.

Size(cms): 27 (H) x 41 (W) x 9 (D)

Size(inches): 10.5 (H) x 16 (W) x 3.5 (D)

-

Andhra Pradesh (South India)

Wood

These horse brackets once formed the two ends of a door lintel. The horse or ashva was a very popular motif in architectural wood carvings in South India. Its prototype, the divine Uchchaihshravas emerged from the churning of the ocean. It was white and endowed with wings. The god Indra appropriated it and, after cutting its wings to ensure that it would remain on earth, donated it to mankind.

The horse played a pivotal role in establishing the supremacy of kings, as demonstrated, for instance by the great horse sacrifice, the Ashvamedha, which might have been established in the course of the Vedic period. Equestrian motifs appear prominently in Indian art, for example in Orissan sculpture of the 12th and 13th centuries, and in that of the late Vijaynagara and Nayak periods (early 16th to early 18th century) in southern India. There is a branch of literature specialising in the training of horses, which contains detailed passages on colouring, proportions, gait, auspicious and inauspicious marks and lists of appropriate names for horses.

Individual Sizes (cms): 36 (H) x 61 (W) x 15 (D)

Individual Sizes (inches): 14.2 (H) x 24 (W) x 5.9 (D)

-

Andhra Pradesh (South India)

Wood

These horse brackets once formed the two ends of a door lintel. The horse or ashva was a very popular motif in architectural wood carvings in South India. Its prototype, the divine Uchchaihshravas emerged from the churning of the ocean. It was white and endowed with wings. The god Indra appropriated it and, after cutting its wings to ensure that it would remain on earth, donated it to mankind.

The horse played a pivotal role in establishing the supremacy of kings, as demonstrated, for instance by the great horse sacrifice, the Ashvamedha, which might have been established in the course of the Vedic period. Equestrian motifs appear prominently in Indian art, for example in Orissan sculpture of the 12th and 13th centuries, and in that of the late Vijaynagara and Nayak periods (early 16th to early 18th century) in southern India. There is a branch of literature specialising in the training of horses, which contains detailed passages on colouring, proportions, gait, auspicious and inauspicious marks and lists of appropriate names for horses.

Individual Size (cms): 40(H) x 64(W) x 18(D)

Individual Size (inches): 15.5(H) x 25(W) x 7(D)

-

Andhra Pradesh (South India)

Wood, polychromed

These horse brackets once formed the two ends of a door lintel. The horse or ashva was a very popular motif in architectural wood carvings in South India. Its prototype, the divine Uchchaihshravas emerged from the churning of the ocean. It was white and endowed with wings. The god Indra appropriated it and, after cutting its wings to ensure that it would remain on earth, donated it to mankind.

The horse played a pivotal role in establishing the supremacy of kings, as demonstrated, for instance by the great horse sacrifice, the Ashvamedha, which might have been established in the course of the Vedic period. Equestrian motifs appear prominently in Indian art, for example in Orissan sculpture of the 12th and 13th centuries, and in that of the late Vijaynagara and Nayak periods (early 16th to early 18th century) in southern India. There is a branch of literature specialising in the training of horses, which contains detailed passages on colouring, proportions, gait, auspicious and inauspicious marks and lists of appropriate names for horses.

Size individual (cms): 47 (H) x 10 (W) x 23 (D)

Size individual (inches): 18.5 (H) x 4 (W) x 9 (D)

-

Andhra Pradesh (South India)

Wood, extensively polychromed

These horse brackets once formed the two ends of a door lintel. The horse or ashva was a very popular motif in architectural wood carvings in South India. Its prototype, the divine Uchchaihshravas emerged from the churning of the ocean. It was white and endowed with wings. The god Indra appropriated it and, after cutting its wings to ensure that it would remain on earth, donated it to mankind.

The horse played a pivotal role in establishing the supremacy of kings, as demonstrated, for instance by the great horse sacrifice, the Ashvamedha, which might have been established in the course of the Vedic period. Equestrian motifs appear prominently in Indian art, for example in Orissan sculpture of the 12th and 13th centuries, and in that of the late Vijaynagara and Nayak periods (early 16th to early 18th century) in southern India. There is a branch of literature specialising in the training of horses, which contains detailed passages on colouring, proportions, gait, auspicious and inauspicious marks and lists of appropriate names for horses.

Individual Sizes (cms):28(H) x 10(W) x 13(D)

Individual Sizes (inches): 11(H) x 4(W) x 5(D)

-

Tamil Nadu

Wood

A pair of extremely fine and large carved and pierced doorway brackets, from the entrance door of a Chettinad mansion. They depict a dense arrangement comprising elaborately caparisoned rearing horses with turbaned and ornamented riders holding whips in the upper register. The pointed turbans worn by these riders is an indication of their royal status. The raised forelegs of the horses rest on the heads of rearing Vyalis – open mouthed and with bulging eyes, who in turn are supported by the trunks of diminutive elephants. At the lower end are parrots perched vertically. The remarkable density of the composition is achieved by filling almost every available space with swirling foliage.

Size individual (cms): 96 (H) x 31 (W) x 15 (D)

Size individual (inches): 37.8 (H) x 12.2 (W) x 6 (D)

-

Gujarat (Western India)

Wood with polychrome

An unusual and impressive set of carved makara brackets (architectural struts) probably originally from the upper pavilion of a mansion or temple. Their open mouths reveal rows of prominent teeth, the upper jaw is formed as a short upturned trunk. The necks have a linked chain, the lower body is encompassed by scales resembling a fish and have an upturned tail.

The Makara is a mythical aquatic creature that is said to combine the body of a crocodile with the head of a lion and the trunk of an elephant. One of India’s most ancient symbols, harking back more than two thousand years to a time when the natural world was seen as both symbol and reality, and fantastic creatures were invented to express the complexity of nature. The Makara is considered auspicious and purifying by Hindus and related to fertility. He is the vehicle (vahana) of Varuna, god of the waters of heaven and earth, and the emblem of Kama, the god of love.

Individual Sizes (cms): 155(H) x 38(W) x 21(D)

Individual Sizes (inches): 61(H) x 15(W) x 8.5(D)

-

Karnataka

Wood, extensively polychromed

An eye-catching folk elephant vahana that would have been a part of a processional figure depicting the Goddess Durga. The carefully painted frontal features, including the head, trunk, and ears, suggest that the elephant was intended to be displayed headlong, while the back half was designed with functionality in mind, ensuring balance for the deity placed on top.

Every year, during Navratri, processional images of the Goddess are carried in evocative ceremonies. Depending on the day of the festival, her vahana, the vehicle on which she rides changes, with each of her vehicles holding a different and unique significance. The elephant she rides here signifies happiness and prosperity.

Size (cms): 29(H) x 41(W) x 20.5(D)

Size (inches): 11.5(H) x 16(W) x 8(D)

-

Karnataka

Wood, extensively polychromed

A charming pair of painted wooden lions with bulging eyes and prominent ‘sunburst’ manes. Laying in a prone positions, their fore and hind legs are well carved and terminate in large claws.

The lion holds a special significance in Hindu mythology, being the sacred vehicle of the goddess Durga. Often regarded as India’s embodiment of Mother Nature, Durga symbolizes energy and vitality. Lions, in Hindu iconography, represent attributes like power, royalty, and nobility. They are frequently portrayed as guardians and protectors in various mythological narratives.

Size (cms): 21.5(H) x 32.5(W) x 13(D) each

Size (inches): 8.5(H) x 13(W) x 5(D) each

-

Karnataka

Wood, polychromed

A delightful, richly polychromed pair of rearing tiger brackets. The wide-eyed tigers have large open mouths, exposing their fangs and long, protruding tongues. They stand on their hind legs, and their muscular torsos are painted with red and black bubris (stripes). Their forelegs are raised, as if poised to pounce, and swirling foliage sprouts from their raised paws.

The tiger is the vehicle of, and sacred to, the Hindu goddess, Durga. From a certain perspective she is India’s Mother Nature, for she is the deification of Energy. Her consort, Shiva, sometimes evoked as Shambo, wears a tiger skin to indicate that he is beyond the bounds of the natural world.

Individual Sizes (cms): 44.5(H) x 22(W) x 10(D) each

Individual Sizes (inches): 17.5(H) x 8.5(W) x 4(D) each

-

Karnataka

Wood

A finely carved pair of double sided yali architectural brackets. The rearing lions with muscular torso’s have swirling foliage spouting from their open mouths.

‘Yali’ or ‘Vyala’ denotes a mythical lion faced animal that appears on carved friezes on temple walls. They are fierce, leonine beasts with curvaceous bodies and enlarged heads surrounded by flame-like manes. They rear up on hind legs, the forelegs held out with clenched claws as if to pounce. Sometimes they are shown standing on human heads presumably of the demons that they have vanquished. In southern Indian sculpture from the 16th century onwards figures of rearing, almost three dimensional vyalis bearing heads either of horned lions or elephants and feline bodies guard the entrances of temples and line the approaches leading to sanctuaries.

Individual Sizes (cms): 74.5(H) x 31(W) x 10(D) each

Individual Sizes (inches): 29.5(H) x 12(W) x 4(D) each

-

Karnataka

Wood, extensively polychromed

This striking large Tiger Vahana with an unusual, prominent flowing mane. The tiger has wide bulging eyes and an open mouth with large exposed teeth and a long protruding tongue. His fore legs are raised, as if to pounce.

The tiger is the vehicle of, and sacred to, the Hindu goddess, Durga. From a certain perspective she is India’s Mother Nature, for she is the deification of Energy. Her consort, Shiva, sometimes evoked as Shambo, wears a tiger skin to indicate that he is beyond the bounds of the natural world.

Size (cms): 61(H) x 38(W) x 27(D)

Size (inches): 24(H) x 15(W) x 10.5(D)

-

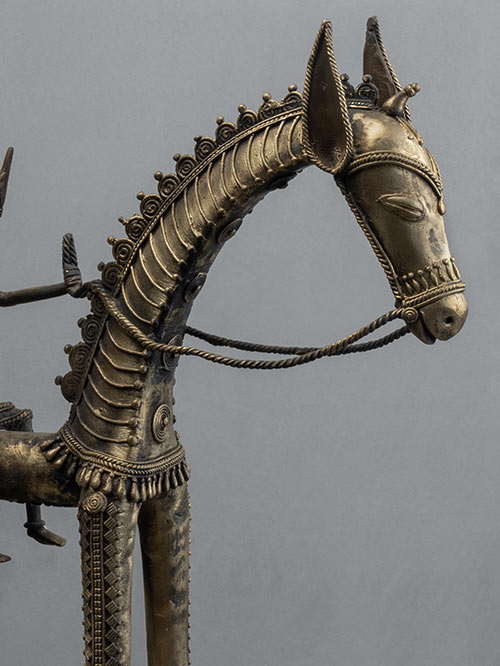

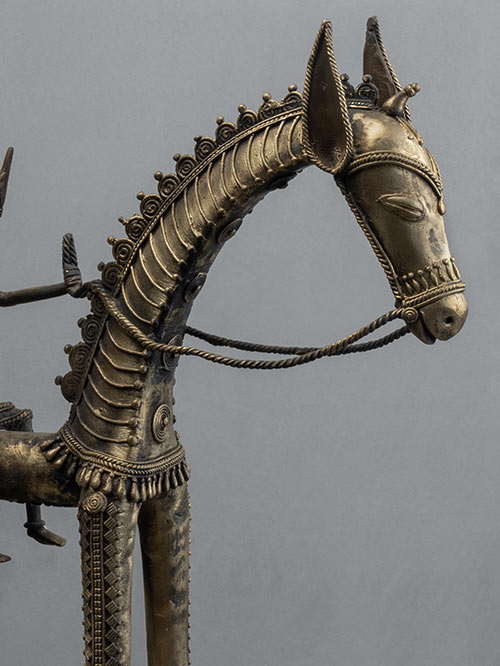

Bastar (Chhattisgarh, Central India)

Brass, Dokra work

A fine sculpture of a horse and four riders (hunters). The figures carry a spear, mace, club and a crocodile.

Suresh Waghmare (signed)

Born in 1970 in a Maharashtrian family in Bastar district, he began to study the technique of Bell Metal Casting with Guru Phool Singh Bisara when he was twelve. Since then he has been working as a member of the co-operative of craftsmen. He is a master craftsman in the art of metal casting and has participated in many international exhibitions.

Size (cms): 51(H) x 84.5(W) x 9(D)

Size (inches): 20(H) x 33.5(W) x 3.5(D)

-

Bastar (Chhattisgarh, Central India)

Brass, Dokra work

Nandi or nandin means rejoicing, gladdening. It is the name of shivas conveyance (vahana) the white bull, son of kashyapa and of surabhi. Nandii was probably a folk deity later incorporated into the brahamanic lore. Nandi symbolises on the one hand moral and religious duty (dharma) , and on the other, virility, fertility and strength. Apart from being shivas vehicle, nandi in his form as nandikeshvara, depicted as a human with a bulls head, is believed to be one of the great masters of music and dancing. In southern India his recumbent image is placed either opposite the main sanctuary or in the hall leading to it, facing the linga.

Suresh Waghmare (signed)

Born in 1970 in a Maharashtrian family in Bastar district, he began to study the technique of Bell Metal Casting with Guru Phool Singh Bisara when he was twelve. Since then he has been working as a member of the co-operative of craftsmen. He is a master craftsman in the art of metal casting and has participated in many international exhibitions.

Size (cms): 38(H) x 81(W) x 10(D)

Size (inches): 15(H) x 32(W) x 4(D)